ROMAN

BRITAIN

The history of “Britain” begins in

55 BC when Julius Caesar led the first

Roman expeditions to the island. Governor of the Roman province of

Gaul, Caesar was upset to find that the Celtic Gauls were getting aid from

their fellow Celts (the Belgae) in

Britain. Caesar had heard that Britain was rich in grain and precious

metals and he hoped the addition of Britain to the Roman Empire would increase

the wealth and glory he had already won by his Gallic campaigns.

Caesar mounted two brief expeditions

against Britain. The first in 55 BC was a fiasco (despite the fact

that he had brought two Roman legions or some 10,000 men across the channel,

he would later describe this expedition in his Commentaries as a “reconnaissance”).

The second in 54 BC had some success, as one of the main British kings

agreed to become a client of Rome and the defeated Britons agreed to pay

tribute to Rome (a promise they soon forgot). But Caesar had to return

to Gaul in 54 BC. Civil War broke out in Rome a few years later,

and his projected conquest of Britain was shelved.

Almost

a century later, however, the Emperor Claudius

revived the idea. In 43 AD he ordered a Roman army into Britain.

For personal reasons, Claudius needed a quick military victory, and Celtic

mistreatment of Roman allies gave him the excuse he needed. The great

British king Cunobelin (Shakespeare’s

Cymbeline) had died in 42 AD, and his sons who succeeded him immediately

went to war against the King of the Atrebates, a Roman ally. Claudius’

forces quickly subdued the tribes of the Southeastern lowlands. Eleven

British kings submitted to the emperor and became his “clients,” ruling

their former kingdoms in the name of Rome. The Romans had a much

harder struggle with the tribes of the Northwest, mainly because of the

more rugged terrain. Still, within 35 years, they occupied all of

“England and Wales” and penetrated into “Scotland.” Most historians

see the Claudian invasion as the real beginning of Roman Britain.

And because the Romans were literate, British history starts with their

arrival.

Almost

a century later, however, the Emperor Claudius

revived the idea. In 43 AD he ordered a Roman army into Britain.

For personal reasons, Claudius needed a quick military victory, and Celtic

mistreatment of Roman allies gave him the excuse he needed. The great

British king Cunobelin (Shakespeare’s

Cymbeline) had died in 42 AD, and his sons who succeeded him immediately

went to war against the King of the Atrebates, a Roman ally. Claudius’

forces quickly subdued the tribes of the Southeastern lowlands. Eleven

British kings submitted to the emperor and became his “clients,” ruling

their former kingdoms in the name of Rome. The Romans had a much

harder struggle with the tribes of the Northwest, mainly because of the

more rugged terrain. Still, within 35 years, they occupied all of

“England and Wales” and penetrated into “Scotland.” Most historians

see the Claudian invasion as the real beginning of Roman Britain.

And because the Romans were literate, British history starts with their

arrival.

The Romans were not seeking a homeland,

but another province to exploit for tribute. They imposed heavy taxes

on the Celts and interfered with their traditions. The Celts revolted

often in the early years. As the Roman historian Tacitus noted, “The

Britons bear conscription, the tribute and their other obligations to the

empire without compliant, provided there is no injustice. That they

take extremely ill; for they can bear to be ruled by others but not to

be their slaves.” The greatest revolt was led by a woman, Boudicca,

Queen of the Iceni (She had been flogged and her daughters raped

by the Roman officials). In 60 AD she inspired a Celtic rising which

defeated one of the Roman legions and captured the key Roman towns of London

and Colchester and burned and pillaged much of Southern Britain.

Some 70,000 Romans and their allies were killed. The revolt was crushed,

however, when another Roman legion was recalled from Wales and annihilated

Boudicca’s army.

Boudicca’s revolt brought some amelioration

in Roman rule. Eventually, some of the Celtic aristocracy even became

Roman citizens, learned Latin, and adopted Roman dress and lifestyles.

This Romanized British culture was largely confined to the South.

In the North, Roman control was always weaker: it was more of a military occupation designed to keep the wilder Celtic tribes

(Picts and Scots)

from raiding the South. Indeed, the problem of controlling the tribes

of the North led the Romans to build their most impressive monument in

Britain – Hadrian’s Wall. Built

between 122-133 AD under the direction of Emperor Hadrian, the wall was

73 miles long, 15 feet high, and 10 feet wide at the base, incorporating

numerous outposts, camps, and fortresses.

more of a military occupation designed to keep the wilder Celtic tribes

(Picts and Scots)

from raiding the South. Indeed, the problem of controlling the tribes

of the North led the Romans to build their most impressive monument in

Britain – Hadrian’s Wall. Built

between 122-133 AD under the direction of Emperor Hadrian, the wall was

73 miles long, 15 feet high, and 10 feet wide at the base, incorporating

numerous outposts, camps, and fortresses.

Near the end of the 3rd century, the

Roman Peace was threatened by new barbarians. “Saxon”

pirates based in what is now the Netherlands, began raiding the Southeastern

coast. To defend against these raids the Romans built a series of

coastal forts later known as the Saxon Shore Forts.

They also established a fleet to intercept the raiders at sea. These

efforts worked for a time, but they meant weakening defenses on the northern

frontier. In 367 the Romans suffered a crushing defeat when the Picts

and Scots coordinated an attack with the Saxons. Reinforcements arrived

quickly from Rome, and the Romans recovered from the defeat. But

within a few decades the Western Empire was crumbling from factional struggles

within and barbarian attacks from without. In 410 the Germanic Goths

sacked Rome itself.

As Rome crumbled, so too did Roman

Britain. Troops were constantly being withdrawn to defend Rome or

help some general seize the imperial throne. By the early 5th century,

the last Roman legions had departed, never to return. The Britons,

used to Roman protection, were left to defend themselves against the barbarians.

Despite a Roman presence of almost

400 years, the Roman influence on British history was not as deep and lasting

as one might think. For one thing, the Romans made up only a small

proportion (5-10 percent) of the population (guestimates: 4-6 million),

and their cultural influence was largely confined to urban areas in the

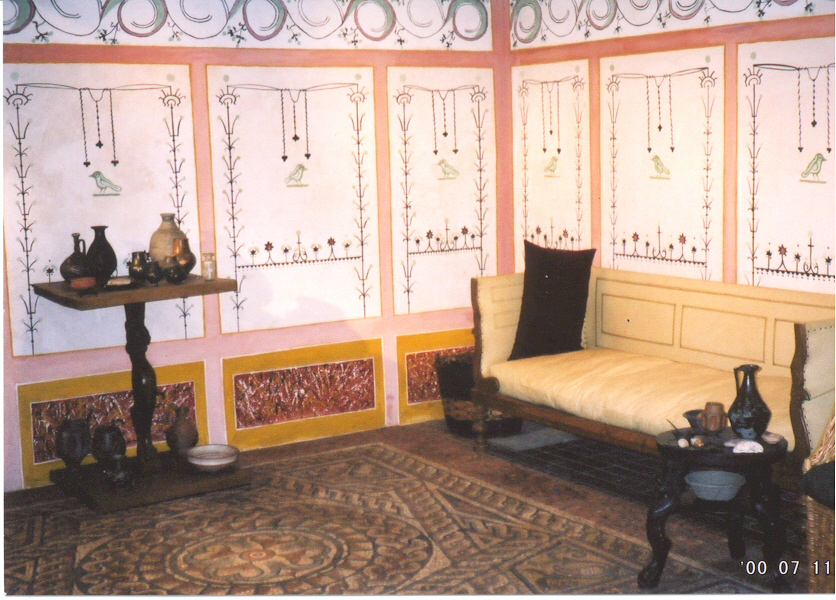

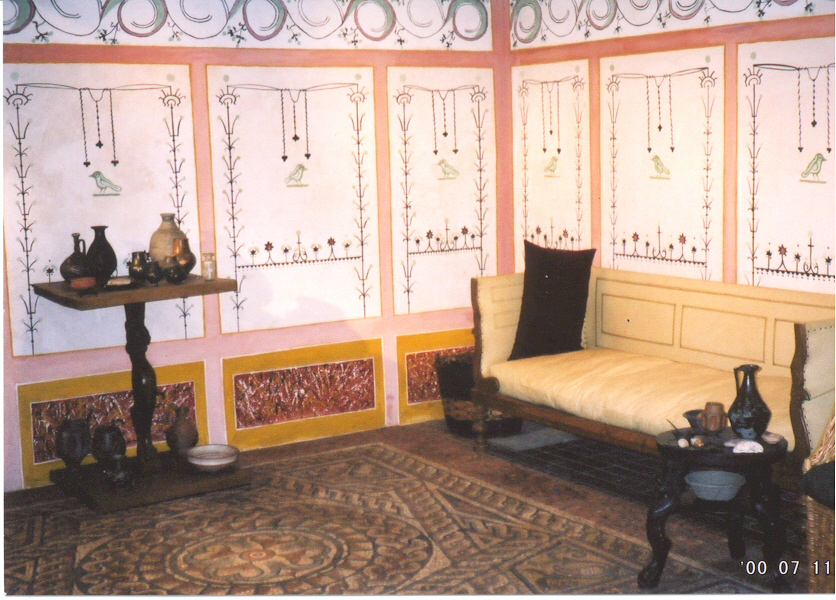

South. The physical evidence of the Roman presence is one of the longest

lasting  legacies,

of course. The Romans were an urban people, and they created scores

of towns and cities. Among these were London,

York, and Bath.

Others were Chester, Colchester,

and all the other towns with caster or chester in them (castra was Latin

word for camp). Wealthy Romans also built large country houses called

villas, many decorated with beautiful mosaic floors and endowed with central

heat and indoor plumbing – things Britain wouldn’t see again until the

19th century. The Romans also built a network of paved roads across

Britain. Although they were badly neglected after the Anglo-Saxon

invasions, they remained the best roads in England until the 18th century.

legacies,

of course. The Romans were an urban people, and they created scores

of towns and cities. Among these were London,

York, and Bath.

Others were Chester, Colchester,

and all the other towns with caster or chester in them (castra was Latin

word for camp). Wealthy Romans also built large country houses called

villas, many decorated with beautiful mosaic floors and endowed with central

heat and indoor plumbing – things Britain wouldn’t see again until the

19th century. The Romans also built a network of paved roads across

Britain. Although they were badly neglected after the Anglo-Saxon

invasions, they remained the best roads in England until the 18th century.

The most important Roman legacy was

Christianity. When the Romans

first came to Britain, they worshiped a large pantheon of gods. They

introduced these to the Celts and added some Celtic gods to the Roman pantheon.

The Romans did not force their religion on the Celts, but they did suppress

the Druids who were a focus of resistance against the Romans. Christianity

came to Roman Britain sometime in the 2nd or 3rd century with Roman soldiers.

At that time it was just one of several cults competing for the faith of

the empire’s citizens. During the early 4th century the Emperor Constantine

decreed toleration for Christianity. By then it was the dominant

religion of the Empire. In the late 4th century it became the official

religion. By the time the Romans left, Christianity was the chief

religion of the Britons. The Anglo-Saxon invasions nearly wiped it

out. But it managed to survive among the Britons in a few remote

corners of the island and spread to Ireland. Celtic missionaries

from Ireland later played an important part in the conversion of the Anglo-Saxons

to Christianity.

RETURN TO HIS 499 SYLLABUS

RETURN TO HIS 599 SYLLABUS

Almost

a century later, however, the Emperor Claudius

revived the idea. In 43 AD he ordered a Roman army into Britain.

For personal reasons, Claudius needed a quick military victory, and Celtic

mistreatment of Roman allies gave him the excuse he needed. The great

British king Cunobelin (Shakespeare’s

Cymbeline) had died in 42 AD, and his sons who succeeded him immediately

went to war against the King of the Atrebates, a Roman ally. Claudius’

forces quickly subdued the tribes of the Southeastern lowlands. Eleven

British kings submitted to the emperor and became his “clients,” ruling

their former kingdoms in the name of Rome. The Romans had a much

harder struggle with the tribes of the Northwest, mainly because of the

more rugged terrain. Still, within 35 years, they occupied all of

“England and Wales” and penetrated into “Scotland.” Most historians

see the Claudian invasion as the real beginning of Roman Britain.

And because the Romans were literate, British history starts with their

arrival.

Almost

a century later, however, the Emperor Claudius

revived the idea. In 43 AD he ordered a Roman army into Britain.

For personal reasons, Claudius needed a quick military victory, and Celtic

mistreatment of Roman allies gave him the excuse he needed. The great

British king Cunobelin (Shakespeare’s

Cymbeline) had died in 42 AD, and his sons who succeeded him immediately

went to war against the King of the Atrebates, a Roman ally. Claudius’

forces quickly subdued the tribes of the Southeastern lowlands. Eleven

British kings submitted to the emperor and became his “clients,” ruling

their former kingdoms in the name of Rome. The Romans had a much

harder struggle with the tribes of the Northwest, mainly because of the

more rugged terrain. Still, within 35 years, they occupied all of

“England and Wales” and penetrated into “Scotland.” Most historians

see the Claudian invasion as the real beginning of Roman Britain.

And because the Romans were literate, British history starts with their

arrival.

more of a military occupation designed to keep the wilder Celtic tribes

(Picts and Scots)

from raiding the South. Indeed, the problem of controlling the tribes

of the North led the Romans to build their most impressive monument in

Britain – Hadrian’s Wall. Built

between 122-133 AD under the direction of Emperor Hadrian, the wall was

73 miles long, 15 feet high, and 10 feet wide at the base, incorporating

numerous outposts, camps, and fortresses.

more of a military occupation designed to keep the wilder Celtic tribes

(Picts and Scots)

from raiding the South. Indeed, the problem of controlling the tribes

of the North led the Romans to build their most impressive monument in

Britain – Hadrian’s Wall. Built

between 122-133 AD under the direction of Emperor Hadrian, the wall was

73 miles long, 15 feet high, and 10 feet wide at the base, incorporating

numerous outposts, camps, and fortresses.

legacies,

of course. The Romans were an urban people, and they created scores

of towns and cities. Among these were London,

York, and Bath.

Others were Chester, Colchester,

and all the other towns with caster or chester in them (castra was Latin

word for camp). Wealthy Romans also built large country houses called

villas, many decorated with beautiful mosaic floors and endowed with central

heat and indoor plumbing – things Britain wouldn’t see again until the

19th century. The Romans also built a network of paved roads across

Britain. Although they were badly neglected after the Anglo-Saxon

invasions, they remained the best roads in England until the 18th century.

legacies,

of course. The Romans were an urban people, and they created scores

of towns and cities. Among these were London,

York, and Bath.

Others were Chester, Colchester,

and all the other towns with caster or chester in them (castra was Latin

word for camp). Wealthy Romans also built large country houses called

villas, many decorated with beautiful mosaic floors and endowed with central

heat and indoor plumbing – things Britain wouldn’t see again until the

19th century. The Romans also built a network of paved roads across

Britain. Although they were badly neglected after the Anglo-Saxon

invasions, they remained the best roads in England until the 18th century.